Drowning: The Overlooked Problem.

Is Your Child Truly Safe Around Water?

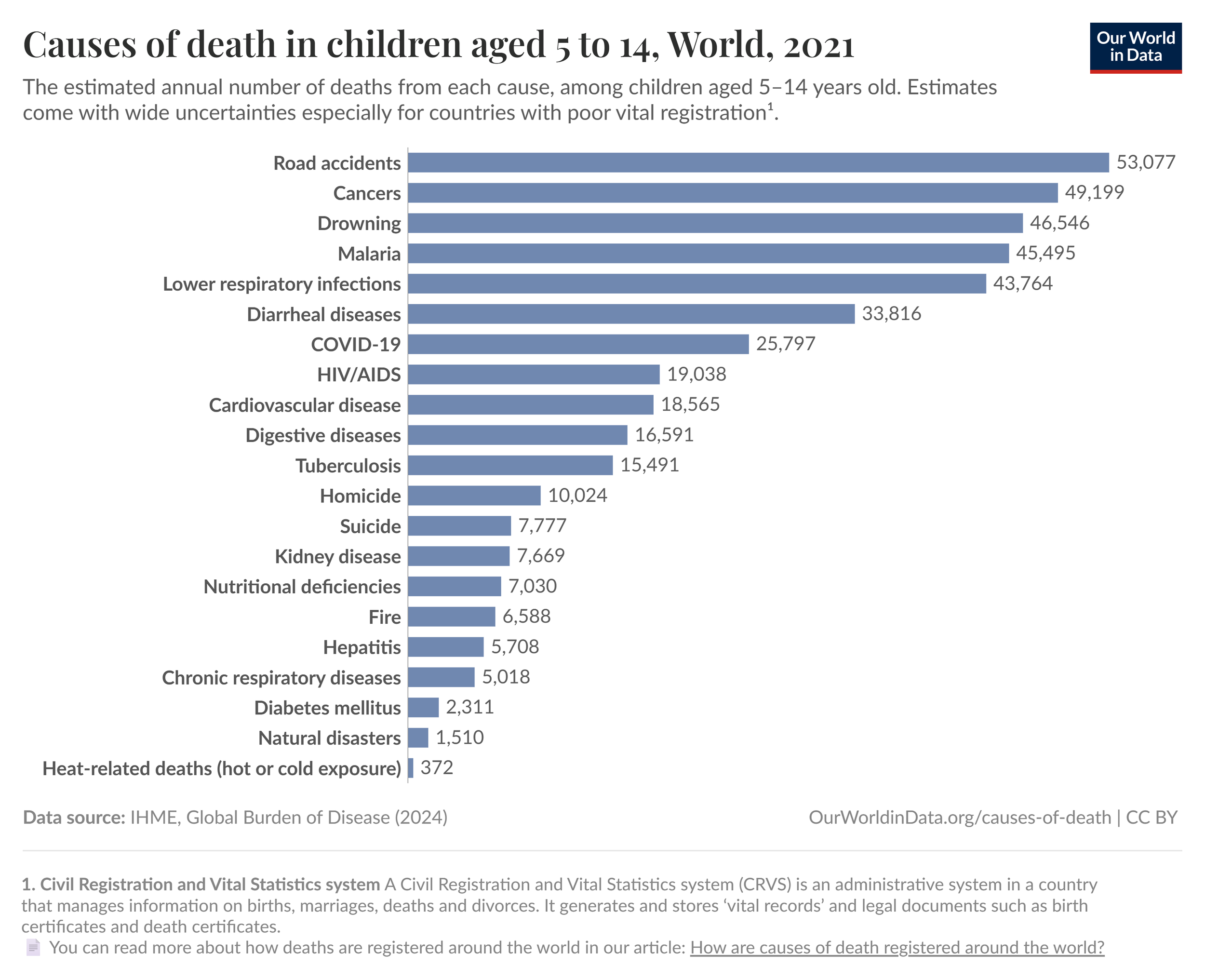

Every summer, families in Lake Stevens flock to the lake, unaware of the dangers the lake brings. Drowning remains the third leading cause of death for children aged 5–14 worldwide, and recent tragedies at Davies Beach have brought this crisis home. This article defines the drowning problem, breaks it down into why drowning happens, who’s most at risk, and—most importantly—what you can do as a parent in our community to keep your child safe. Whether you're here to learn, take action, or find the right swim lessons, you're in the right place.

Section 1. What Defines the Problem?

1.1 Where Is Child Drowning Happening Most?

Drowning disproportionately affects low and middle-income countries (LMICs), which account for over 90% of global child drowning deaths according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Regions like Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific—including countries such as Bangladesh and Vietnam—experience the highest rates, where drowning is the leading cause of death for children aged 5–14. In Bangladesh alone, an estimated 30 to 46 children die every day by drowning in ponds and waterways near their homes says a study from John Hopkins.

In rural areas like Sundarbans, West Bengal, children often play near open water without supervision—putting them at high risk of drowning. Pictured is a few young boys playing with a soccer ball near open water.

1.2 Who Is Most at Risk?

Children most at risk include young boys, who are twice as likely to drown as girls due to increased exposure to water and risk-taking behavior (WHO). Rural and low-income children in LMIC’s live near open water and are unsupervised most of the time, which significantly increases their risk. According to a report by the CDC, ethnic minority children in wealthier places similar to Washington State, face higher drowning rates due to unequal access to swim lessons and safety education. Children with disabilities, particularly autism and epilepsy, face exceptionally high risks—autistic children are 160 times more likely to die by drowning than their peers.

1.3 Who Is Failing to Prevent These Drownings?

Despite the fact that drowning has significant global impact for children aged 5-14, this has been overlooked. According to the a WHO report in 2008, many governments lack national drowning prevention strategies, and global institutions are slow to act.

1.4 Why It Matters in Washington State

Even in a wealthy area like Washington, drowning is a serious concern. According to the Seattle Children’s Hospital on average, 17 children drown each year in the state. The majority of these—89% among children over five—happen in natural bodies of water like as lakes and rivers. Families from immigrant, minority, or low-income backgrounds don’t have access to water safety resources like swim lessons, similar to global trends.

Section 2. What Causes It?

2.1 Why Is Drowning Happening in the Most-Affected Locations?

In rural communities throughout Asia and Africa, children are constantly exposed to open water sources without proper safety measures or supervision. Seasonal flooding and a lack of infrastructure only makes this risk higher. Many of these communities also don’t have access to swim lessons, leaving children with no plan if they find themselves in a water emergency.

2.2 Why Are Certain Children More Vulnerable?

Culture norms in the West Pacific allow young boys to make more risky decisions, contributing to their higher drowning rates¹⁵. Poverty prevents families from affording swim lessons or putting barriers around bodies of water. In the U.S., low-income families disproportionately have worse swimming abilities. Children with conditions such as autism or epilepsy may not recognize water dangers or may be unable to call for help, placing them at extremely high risk of fatal drowning incidents.

2.3 Why Are Prevention Systems Failing?

A lack of political will and public awareness has allowed drowning to be swept under the rug by governments. Faulty and underdeveloped data collection has also prevented governments from coming up with coordinated responses.

2.4 Why Is There a Link to Washington?

Washington’s many lakes and rivers are beautiful but pose real danger. Cold water, strong currents, and unexpected drop-offs create risks even for experienced swimmers. Lake Stevens recently reported a confirmed fatality of a 12 year old boy by drowning. A tragic, horrific incident for any parent to face.

A gorgeous view of Lake Crescent, Washington. Drownings have been reported many times.

Section 3. What’s Being Done?

3.1 Interventions in High-Risk Regions

To address the crisis in high-risk areas, programs like Bangladesh’s community daycares have been launched to supervise young children while caregivers are occupied. The SwimSafe program teaches basic survival swimming skills to thousands of children in LMICs. Some areas have implemented physical safety measures such as well covers and fencing to reduce exposure to open water.

3.2 Interventions for Vulnerable Groups

In the U.S., adaptive swim lessons tailored to the needs of autistic children are becoming more widespread, like at the Snohomish Aquatic Center. Even small businesses like LifeLong Aquatics are following this trend. Initiatives like the Make a Splash program are working to provide affordable swim lessons to those who cannot afford it.

3.3 Strengthening Global and National Systems

Global organizations are now taking action. The UN and WHO have released resolutions calling for coordinated global drowning prevention efforts. Countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh have adopted national safety plans to integrate swim education and awareness into their public health strategies. In the U.S., local governments have introduced programs like life jacket loaner stations to increase safety near bodies of water. This is promoted and shown to parents on the Washington State Parks website.

3.4 Local Applications in Washington

Washington has implemented some of these solutions, including public awareness campaigns, life jacket stations at lakes, and life jacket loaner stations. However, more needs to be done ensure safety, particularly in lower-income families that don’t have access to swim lessons.

Section 4. What Can You Do?

4.1 Teach Your Child to Swim—Early

Get your child into swim lessons as early as possible. Adaptive programs are available for children with special needs and can offer life-saving skills. Snohomish Aquatic Center and LifeLong Aquatics both offer these services with certified instructors, ensuring high quality.

4.2 Make Life Jackets the Norm

Life jackets aren’t just for boating. Make sure your child is wearing one any time they’re near deep or unpredictable water. The last thing any parent wants is for their child to be a victim of the water.

4.3 Watch, Don’t Walk Away

Always have a responsible adult to actively supervise when children are in or around water. It is common practice that children under 6 cannot be left alone in the water, like at Snohomish Aquatic Center.

4.4 Support Community Action

Drownings at Lake Stevens have taken young lives in recent years—but we as a community can change that. Advocate for more signage and supervision at Davies Beach and other popular swim spots around Lake Stevens. Sign up your child for swim lessons. Teach your child to promote water safety when they are out with friends. Every action you take helps protect the children, starting with your own.

Works Cited.

World Health Organization. "Drowning." World Health Organization, 2024, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drowning.

IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2024) – with minor processing by Our World in Data. “Drowning” [dataset]. IHME, Global Burden of Disease, “Global Burden of Disease - Deaths and DALYs” [original data].

Alonge, O. et al. "Community Daycares Reduce Drowning in Bangladesh." Johns Hopkins International Injury Research Unit, 2020, https://publichealth.jhu.edu/international-injury-research-unit/2020/community-led-daycares-found-to-reduce-drowning-deaths-among-children-9-47-months-old-by-nearly-90-percent-in-bangladesh-study.

WHO. "Sex Differences in Drowning Rates." World Health Organization, 2024, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drowning.

Global Health Advocacy Incubator. "Bangladesh Child Drowning Prevention Project." 2022, https://www.advocacyincubator.org/news/2022-03-24-bangladesh-government-approves-child-drowning-prevention-project.

Gilchrist, Julie and Parker, Erin M. "Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Fatal Unintentional Drownings." MMWR, 2014, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6319a2.htm.

Joseph Guan, Guohua Li, “Injury Mortality in Individuals With Autism”, American Journal of Public Health 107, no. 5 (May 1, 2017): pp. 791-793. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303696

Peden, Margie, et al. World Report on Child Injury Prevention. WHO, 2008.

WHO. "Data Gaps in Drowning Prevention." World Health Organization, 2019, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drowning.

Seattle Children’s Hospital. "Water Safety in Washington." 2023, https://www.seattlechildrens.org/health-safety/injury-prevention/water-safety.

Washington State Department of Health. Child Death Review: Drowning Data. 2012, https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/Documents/2900//DOH530090Drown.pdf.

Moran Kelley PLLC. "Understanding Water Safety in Washington." 2025, https://www.morankelley.com/blogs/understanding-water-safety-and-drowning-risk-in-washington-state.

Yang, Li et al. “Risk factors for childhood drowning in rural regions of a developing country: a case-control study.” Injury prevention : journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention vol. 13,3 (2007): 178-82. doi:10.1136/ip.2006.013409

WHO. "Drowning Risk During Climate Events." World Health Organization, 2024.

Morgan, R. et al. "Disparities in WA Youth Water Safety." Harborview Injury Prevention, 2022.

Columbia Public Health. "Drowning Risk in Autism." 2017.

USA Swimming Foundation. "Make a Splash." 2023.

WHO. "WHA Resolution 76.18." World Health Organization, 2023.

WA DoH. "Life Jacket Loaner Program." 2022.